Let’s take a trip back to a time when India faced one of its biggest tests as a democracy—a period so intense it’s still talked about today. It’s called the Emergency, and it happened from June 25, 1975, to March 21, 1977.

The Spark: Why Did the Emergency Happen?

Picture this: it’s 1971, and Indira Gandhi, India’s Prime Minister, is riding high. She’s just led India to a big win in the war against Pakistan, which helped create Bangladesh. The whole country is chanting her name, calling her the “Iron Lady.” She wins a massive election victory in her constituency, Raebareli, and feels unstoppable. But by 1973, things start to unravel.

Trouble brews in Gujarat, where a famine-like situation and unemployment spark student protests called the Navnirman movement. These protests inspire students in Bihar to rise up too, rallying against Indira’s government. At the same time, a fiery leader named George Fernandes leads a railway strike that paralyzes the country for three months. Three big protests—Gujarat, Bihar, and the railways—are hitting Indira from all sides. She’s feeling the heat.

Then comes a bombshell. In June 1975, the Allahabad High Court rules that Indira cheated in the 1971 election. The court says she should lose her seat in Parliament, and the Supreme Court agrees but lets her stay as Prime Minister with a catch—she can’t vote. Indira’s power is under threat, and she’s not happy.

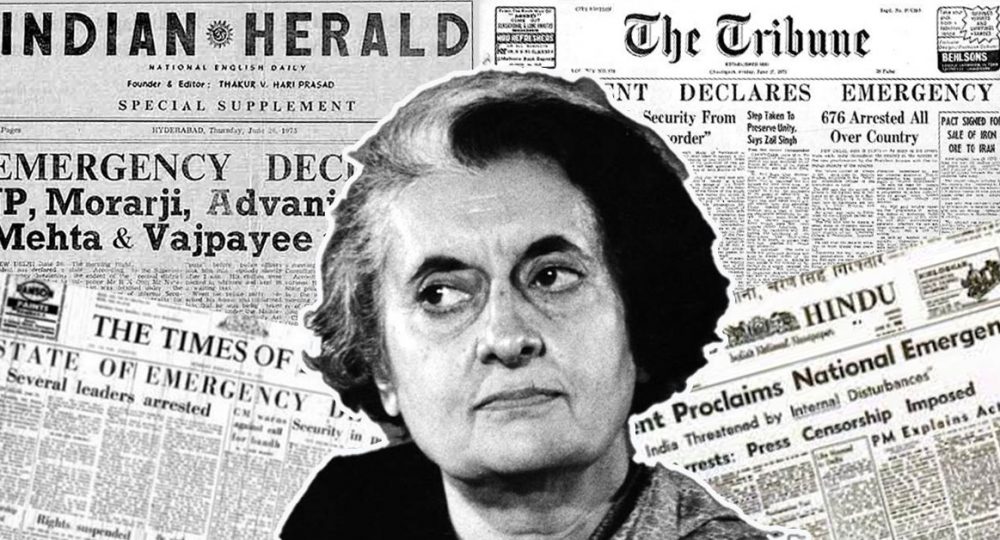

On the morning of June 25, 1975, a massive rally led by a respected freedom fighter, Jayaprakash Narayan (JP), draws lakhs of people to Ramlila Maidan in Delhi. They’re chanting against Indira, demanding change. That night, Indira makes a bold move. Without even consulting her cabinet, she convinces President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed to declare a state of Emergency, using a vague rule in the Constitution about “internal disturbance.” By 3 a.m., the country is in chaos.

The Crackdown: A Democracy on Pause

The Emergency gave Indira’s government sweeping powers. The Constitution allowed it, but what followed was anything but normal. Imagine waking up to find newspapers missing from the stands. Why? Because the government cut electricity to major newspaper offices overnight, stopping them from printing. The Indian Express and Statesman fought back by publishing blank editorials—a silent scream against censorship. Four news agencies were forcibly merged into one called Samachar, and every story had to be approved by a government censor. Critical newspapers lost funding, and some editors were even arrested.

Then came the arrests. By dawn on June 26, police were raiding homes, rounding up opposition leaders like JP Narayan, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, LK Advani, and thousands more. In total, 110,000 people were jailed, including 11,000 political leaders and workers. The government didn’t stop there. Indira’s son, Sanjay Gandhi, took things to another level. He pushed for extreme measures, like banning dowry and caste distinctions—good ideas, but poorly executed. The worst was his forced sterilization campaign. Sanjay believed India’s population was the root of its problems, so his teams rounded up millions, mostly poor people, for forced vasectomies. Some estimates say 8.3 million people were sterilized, often against their will, in camps. It was brutal and left deep scars.

The judiciary took a hit too. Indira’s government passed laws saying Parliament could change the Constitution however it wanted, and courts couldn’t challenge it. They even added “socialist” and “secular” to the Constitution’s preamble during this time. Elections, due in 1976, were postponed, and the Emergency dragged on.

The Fightback: A Coalition is Born

While the country was under lockdown, something incredible was happening in the jails. Leaders from different backgrounds—socialists, communists, right-wing RSS members, and others—were locked up together. For two years, they shared ideas, built bonds, and planned to take on Indira. It was like a college for rebels, forging alliances that would change India’s politics forever.

In 1977, Indira made a surprising move—she ended the Emergency herself. Some say she thought she’d win the next election easily. Others believe she was tired of the isolation or wanted to match Pakistan, which had just ended a similar crisis. Whatever the reason, she released the jailed leaders and called for elections.

Those jailed leaders had formed a new coalition called the Janata Party, uniting groups like Bharatiya Lok Dal, Bharatiya Jana Sangh (a precursor to the BJP), Congress (O) (a breakaway Congress faction), and socialists. They rallied under JP Narayan’s leadership, and in the 1977 election, they pulled off a historic upset. The Janata Party swept North India, winning all 85 seats in Uttar Pradesh, 52 out of 54 in Bihar, and more. Congress was crushed, and Morarji Desai, a Congress (O) leader, became India’s first non-Congress Prime Minister.

The Fallout: A Changed India

The Emergency didn’t just end—it reshaped India. The Janata Party’s victory showed that coalition politics could work, giving rise to regional parties and a more diverse political scene. States gained more power, as the Constitution was changed to stop the central government from dismissing state governments so easily. The judiciary also got stronger, with courts later ruling that the Constitution’s basic structure couldn’t be changed, protecting words like “socialist” and “secular.”

But there was a darker side. The Emergency legitimized the RSS, which had been a fringe group before. Many of its members, including young leaders like Narendra Modi, were jailed and emerged as heroes in the anti-Emergency fight. This gave the RSS a foothold in mainstream politics, eventually leading to the formation of the BJP in 1980. The Emergency also taught people about the dangers of media censorship, as blank editorials and silenced voices became symbols of resistance.

The biggest twist came later. In 1980, Indira Gandhi roared back to power with a massive majority, riding a wave of sympathy and voter frustration with the Janata Party’s infighting. Her son, Rajiv Gandhi, took over after her assassination in 1984. Fearing party Link: party splits, Rajiv introduced the Anti-Defection Law in 1985, a rule that changed Indian politics forever. This law says MPs can’t switch parties unless two-thirds of their party defects with them, and they must vote according to their party leader’s orders. It was meant to stop political flip-flopping, but it turned MPs into “flesh bags with fingers,” voting as their party dictates without debate. Many say this law weakened democracy by giving party leaders too much control.